“One thing that comes with inner peace is that you simply stop caring what anyone thinks of you.”

As the upcoming skate part and the film "Rolling Away" will demonstrate, Sheckler still has something to prove—not to fans or posterity but to himself. It’s been more than three years since these projects were born, and seeing them through has required more perseverance than he could have imagined.

The earliest weeks of filming, which coincided with the start of the pandemic, required significant improvisation, as Sheckler and Ingram sought out some truly isolated spots to nail down clips. Nonetheless, these were intensely productive months, yielding one quality clip after another.

But that early momentum came to a painful and screeching halt three months later in National City, California. Sheckler had his eye on a high-risk ender, a dramatic clip that would appear near the end of his part to showcase his best work, but he suffered a hard landing before he could even give it a shot. Warming up with an easier trick, he launched over a staircase with metal railings on both sides and landed

awkwardly on a sloped concrete embankment, with the brunt of the impact loaded on his left knee. True to form, Sheckler, who says it felt like a “super gnarly deadleg,” kept skating that session, even nailing a couple more tricks. He can admit now that he was in a state of denial; he didn’t get an MRI of that joint for a month and a half after skating those six weeks in a knee brace.

That’s when Sheckler learned he had completely severed his ACL. So it was back to the surgeon and the couch and the PT and the creeping self-doubt. “Ryan isn’t old by any means,” says Ingram. “But still, a torn ACL in your 30s can be a career ender for a pro skater.” Sheckler attacked his rehabilitation to get well as fast as possible. He amped up his weight training to add muscle mass as body armor. He did everything he could to stay busy because it took 14 long months before he could really start doing heavy tricks again. That whole period was tough. He lost his grandmother during that grinding recovery. “She was my best friend,” Sheckler says. He had plenty of reasons to start drinking again. But he didn’t.

By the time he got back at it, so much about his life was reoriented in a different and better way. He was sober and engaged and going to church and doing a lot of little things more mindfully. And he went out with an intense eye to execute tricks that pushed his own envelope. Ingram says Sheckler has been playing with bungees that enable him to launch up features that in the past he would have launched himself down. “We’re using a bungee that’s off the market now because it’s so dangerous,” Ingram says. “It can get Ryan up to 25 or 30 miles per hour.

Sheckler freely admits this quest presses many of the same buttons as any other addiction—not just with the narcotic rush of rolling away from an impossibly hard trick, but all the heartache and tense moments that precede it. “I think I’m just curious still, and I’m also addicted to that adrenaline rush of healthy fear,” he says. “I’m addicted to the whole process. It’s the drive. It’s what music I’m going to listen to on the way down. Sometimes I don’t listen to music; sometimes it’s one song on repeat. It’s all very different and it’s very hard to calculate what the right day is to do it, so everything’s a guess. It’s kind of like the lottery, you know?”

A long day with Sheckler is drawing to a close. His wife is cradling his baby. His mother, who helps run his various business enterprises, sits at the head of the dining room table firing off emails. He is rubbing his eyes. Ryan Sheckler is tired because he spent part of the night half asleep on the floor of the nursery. But he’s feeling alive and well because so many things have fallen into place for him. He’s grateful for that horrible slam in Pomona and how it nudged his trajectory in a better direction. The products of reawakening are all around him.

“It feels like I could’ve missed all of this,” Sheckler says, waving his arms at the family around him and at things that can be felt and not seen. “It feels like I could’ve missed it all. But by changing one thing, which meant I had to change everything, I have a full life again.”

He pauses, then corrects himself.

"We are talking about intense physics—it’s like he’s getting fired out of a cannon.”

"think I’m just curious still, and I’m also addicted to that adrenaline rush of healthy fear.”

"Actually, for the first time, I have a full life.”

In "Rolling Away", a few legendary pros try to describe the abusive relationship committed skaters have with pavement. “Skateboarding is terrible for your body,” says British skate pioneer Geoff Rowley, no stranger to brutal slams. “And it chips away like a hammer and chisel.”

Meanwhile, fellow American icon Tony Hawk (who was a surprise guest at Sheckler’s 6th birthday party) reflects on the commitment that the hammer and chisel demand. “When you first start to skate, there’s sort of a moment of recognition and the threshold, where the first time you get hurt seriously,” says Hawk, who like Sheckler has seen a surgeon or two. “That’s the moment where it’s like, do you really love this enough to keep doing it?”

As "Rolling Away" documents, Sheckler faced two serious injuries in the past five years that challenged his resolve. The first came in 2018 in Pomona, where an attempt to grind the cement railing of an 18-step staircase ended with him crumpled on the ground. He pulverized the bones and tendons in his left ankle and also broke the L1 vertebra in his lower back. “I don’t really talk about this slam because it was so traumatic,” says Sheckler, who soon would be back in a surgical suite.

In his mind, the journey that would lead him to sobriety, the Bible, his wife, a baby, and to skating with new clarity and joy began right there in Pomona, as he recoiled in agony.

Sheckler knew what would come next. Pain. Grinding physical therapy. Creeping self-doubts. He knew that all he could do is obsessively recover and train to be ready when the next opportunity came.

That opportunity came sooner than he or anyone would have guessed. Later in 2018, Sheckler was invited to join fellow Red Bull pros Zion Wright and Jamie Foy on a trip to Taiwan. Even though he wasn’t 100 percent healed, he found himself in a great headspace and would up nailing all sorts of clips. The highlight of that trip came when he pulled off a high-consequence taildrop off a Taipei bridge into a quarterpipe that was flanked on both sides by highway traffic. “That taildrop was as scary as anything he’s ever done,” says Ingram, who filmed the trick. “My hands were literally shaking so I needed to lean against something as I shot it.”

Even top pros were blown away. “One word comes to mind seeing that taildrop: ‘psycho,’ ” says pro Paul Rodriguez, aka P Rod, Sheckler’s longtime former teammate with Plan B. “Like that was insane.”

“But that fall was the catalyst for me to take a deep dive into myself.”

—DAVID REYES

Documentary coming soon...

The part and the film are almost done—but not done. In particular, Sheckler is intensely focused on one trick—it’s a massive gap in northern San Diego County. Maybe he’ll have nailed by the time you read this. Maybe not. “I hope to get this last trick and I believe I will,” he says. “I’m scared of it, you know? But it’s a healthy fear. I cannot let this thing go. And I think that’s what’s made me a skateboarder and that’s why I’m still a skateboarder today.”

Reyes has seen the spot, and he also knows the kind of obsessiveness that can be wrapped around rolling away from a trick that a skater feels certain should end his next part. “The caliber of the spot has this aura,” he says. “With an ender, it has to be the craziest shit you’ve ever done. It has to be monumental, something that will live in the skate books forever. I know where Ryan is at now—it’s like being in a nightmare until you get the trick.”

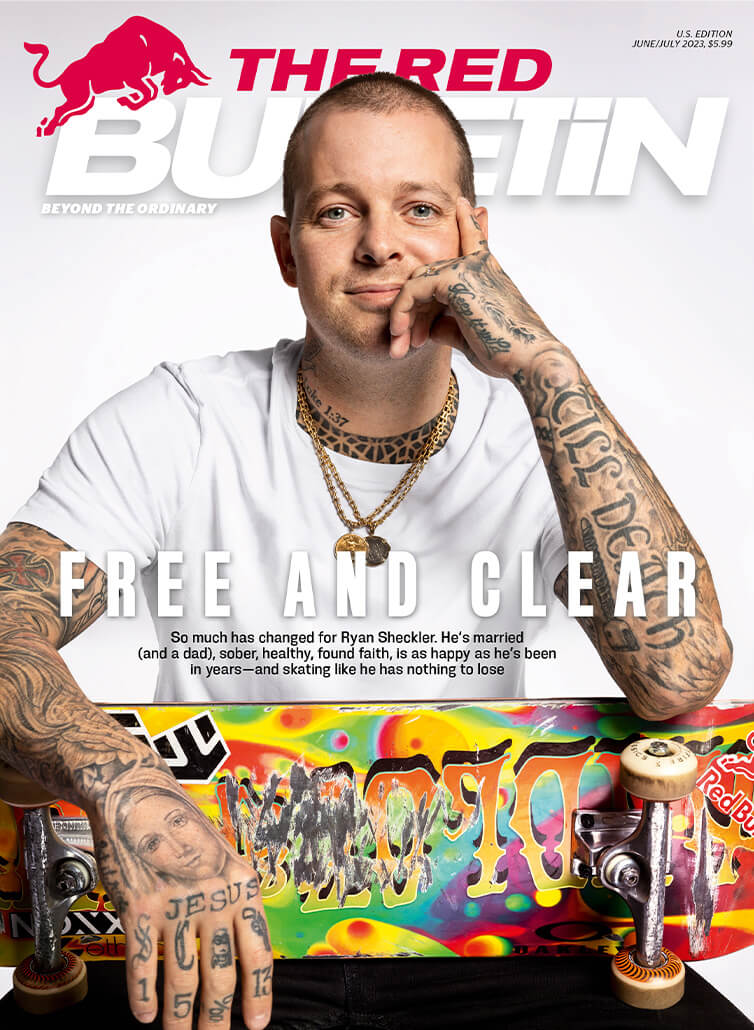

CLEAR

FREE AND

Ryan Sheckler has found something amazing: Himself.

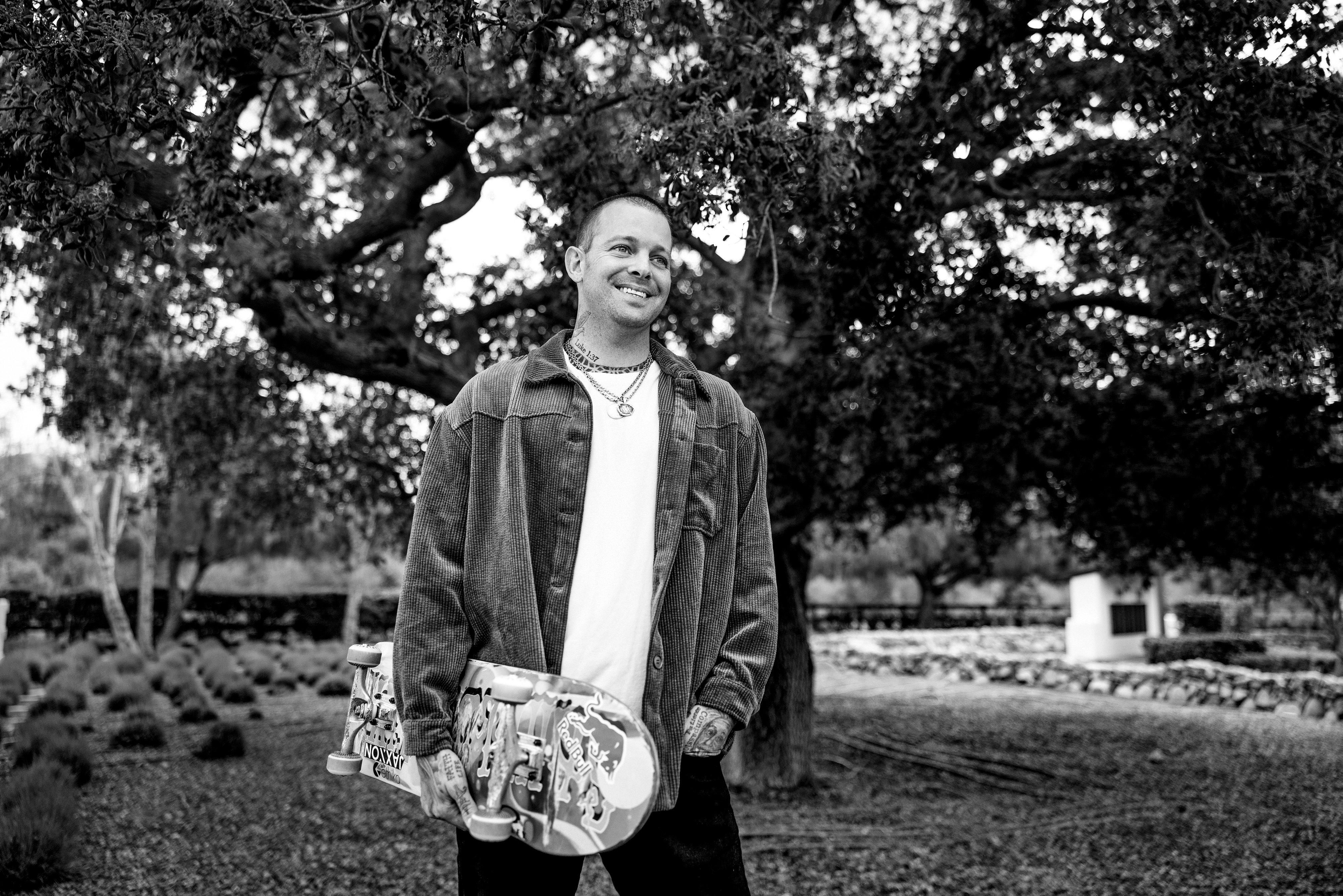

Words: PETER FLAX Photography: ATIBA JEFFERSON

It’s tricky to decide where to begin the story of Ryan Sheckler’s hard-fought journey to find peace.

Maybe it starts with him writhing and screaming at the bottom of a hulking concrete staircase in Pomona, California, as he reels from yet another awful bone-and-tendon-snapping impact. No doubt, the skater’s narrative often has been propelled by how he has willed himself back to his feet after getting pummeled.

Or perhaps it opens with his second trip to rehab. Sheckler had been sober for a few years and thought maybe he could drink with moderation. He was wrong about that. But this time he felt something click inside—a deep yearning to alter the trajectory of his life—and now a very public figure who spent a solid chunk of two decades feeling pretty lost has found a better foothold.

“Life is hard for

a reason—we’rE supposed to learn."

“Inner peace builds confidence,” says fellow skate pro David Reyes, one of Sheckler’s closest friends. “Inner peace allows you to be present in the moment. He’s always been a Nitro Circus baby, someone born to jump off things and take risks, but now Ryan is skating with more confidence than I’ve ever seen.”

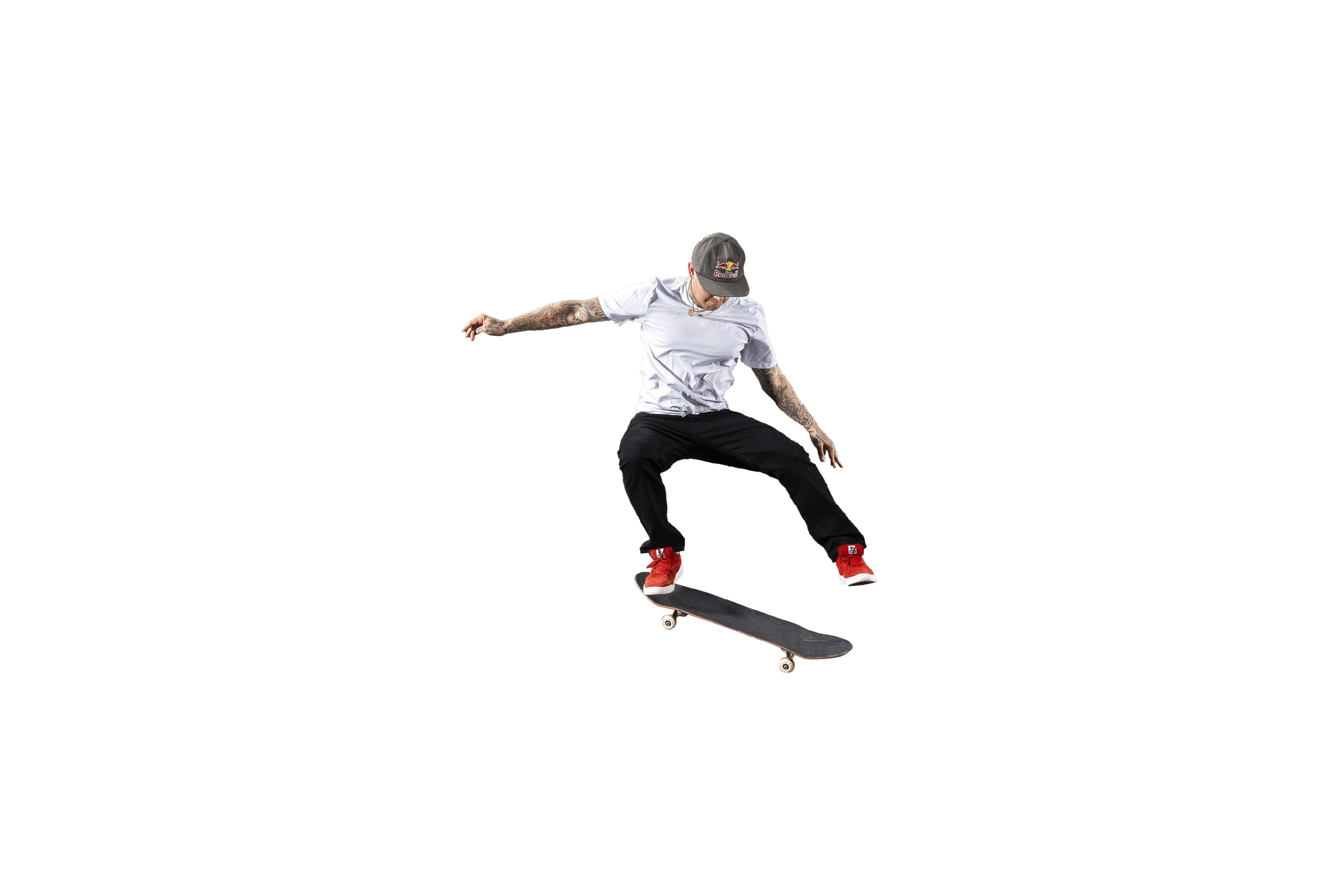

As this story goes live, the finishing touches are being applied to an ambitious skate part and a documentary unpacking Sheckler’s tumultuous journey, aptly called "Rolling Away". Both projects, which are expected to drop in July, have been three years in the making, delayed and informed by the pandemic, an injury that could have been career ending, rehab and the roller-coaster known as life. True to his obsessively perfectionist nature, he’s trying to nail a couple final tricks, including one that would instantly join his greatest hits, before setting that content free. Rest assured that domestic and existential bliss have not quieted Ryan Sheckler’s hunger to explore the boundaries of physics and courage. It’s more like he’s free to go for it.

"INNER PEACE ALLOWS YOU TO BE PRESENT IN THE MOMENT."

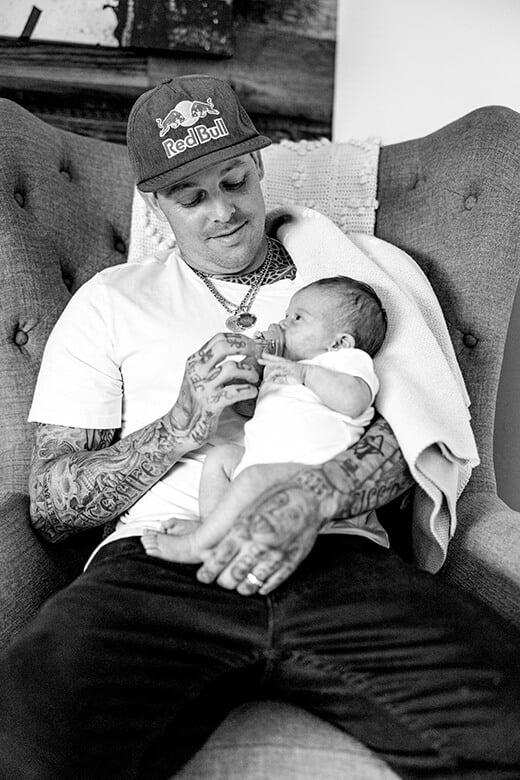

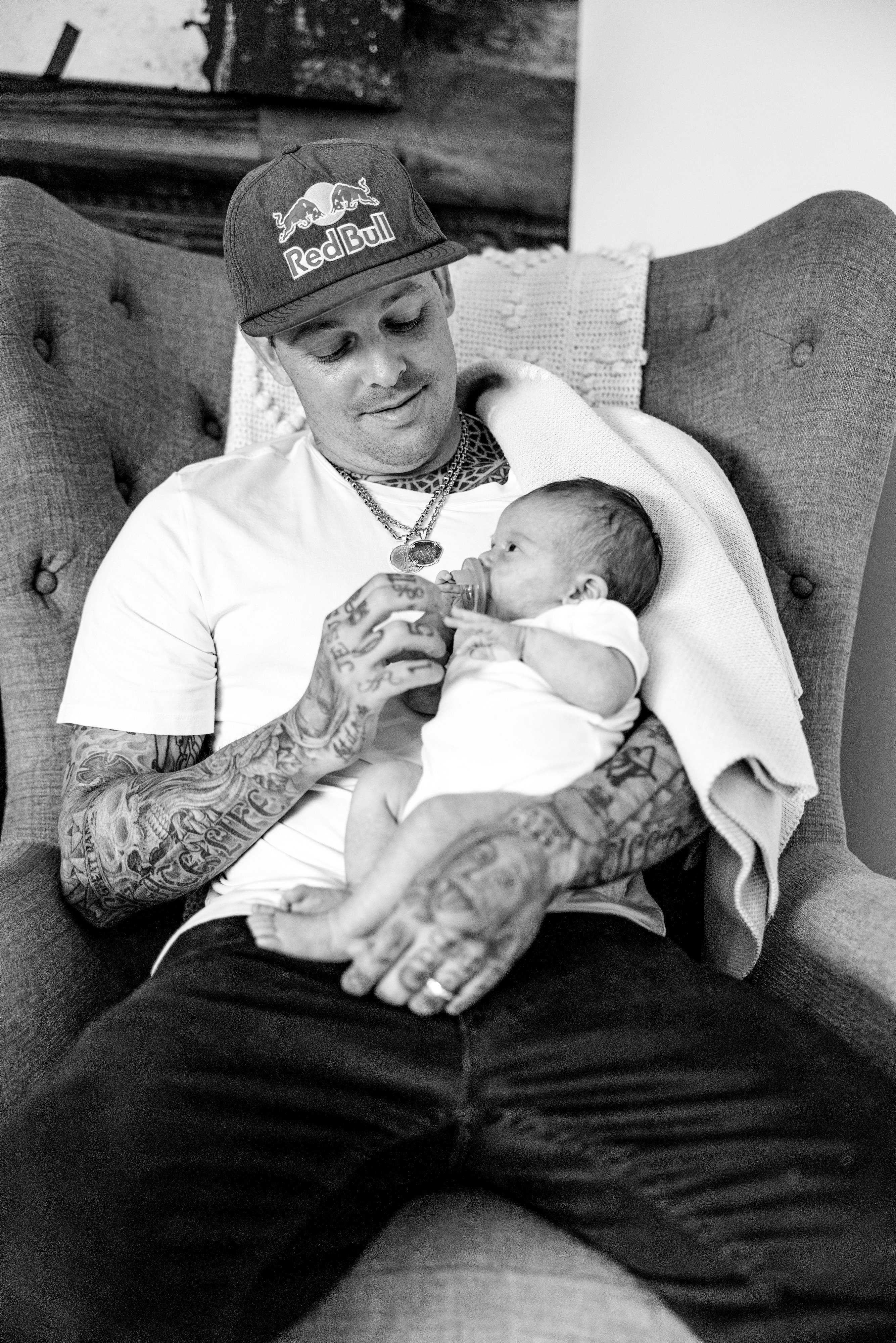

Or maybe the story begins as Sheckler opens the front door to his home with a 19-day-old infant cradled in his right arm. His eyes look a little heavy—after all, the skater and his wife are trapped in a sleep-deprivation experiment—but there’s an ease to his gaze. Like he’s about to launch a huge gap and he just knows he’s going to land it. Somehow, he’s in his element. The guy that friends and fans sometimes called Sheck Daddy has undeniably manifested that title.

"Until recently, my identity—my whole life— has been tied to skateboarding."

Check out Ryan’s new video part Lifer

Photo credit: Tim Aguilar

But while the structure of this story’s prologue remains up in the air, the broader contours of his journey and even his destination are in sharp focus. Ryan Sheckler is in a good place. “Until recently, my identity—my whole life—has been tied to skateboarding,” he says later, as his daughter, Olive, snoozes in a rocker nearby. “I never addressed who Ryan was as a person. And by doing that, all of these doors have opened and all these situations that used to baffle me and take me for a complete loop have beome completely manageable.”

Sheckler, who long ago gained fame for skating the gnarliest shit and acting like a rock star, has turned his gaze inward, finding things he didn’t realize he needed. Sobriety. Faith. Marriage. Fatherhood. Balance. And perhaps above all, peace. You can see it as he holds his baby and whispers in her ear.

And, fans will be stoked to hear, you can see it when he skates. Though it long has been true that Sheckler has nothing to prove, he’s liberated to express himself in ways that feel new. The physical and metaphysical housecleaning has reinvigorated him as a skater. The 33-year-old veteran— who has been performing at the highest level for two decades and helped orthopedic surgeons put their kids through college and juggled as much love and hate from skate culture as any pro ever—is seeing a new clarity and drive in his skating life.

—David Reyes

—RYAN SHECKLER

—RYAN SHECKLER

—RYAN SHECKLER

—Ira Ingram

—Ryan Sheckler

THE PRELUDE

“But everything else is just a brutal divorce, you know? It’s gnarly. I was counting the other day—it’s over 12 broken bones, more torn ligaments than I can remember and six major surgeries, concussions. It’s all pain.”

Sheckler has been through the cycle of injury, surgery and recovery enough times to know how much it can impact his mental health. “I’ve probably spent five years in total of my life recovering,” he admits. “That’s where my mind starts going a little bit crazy and the questions start coming up. ‘Am I made for this? Do I even want this? What am I doing?’ And those questions are super gnarly, especially when you’re already down and you can’t do anything.”

"He’ll skate something until he has baby-deer legs.”

—Ira Ingram

For those seeking context, here’s a 170-word summary: He ripped a kickflip at 6. A year later, he had legit sponsors. He won the first of seven X-Games medals when he was 13. Then came reality shows and TV commercials, A-list fame and millions of dollars. He was skating hard, winning contests and releasing sick clips, flying private jets and collecting supercars and partying hard and polarizing skate culture. He was a teen superstar on a wild adventure with no mentors or a road map, living large with a major IDGAF attitude. (In a 2011 interview with "ESPN The Magazine" he leaned into the friction with core skate fans: “I want to give them more reasons not to like me.”) But through it all, even when folks were dissing him like he was the Justin Bieber of skating, even the biggest haters couldn’t deny that his clips were off the charts. People still talk about his 2008 kickflip at the so-called Costco Gap in Laguna Nigel, clearing a fence and a monstrous 16-foot drop with shocking nonchalance.

Along the way, there were so many huge tricks and huge impacts. “He’s got a crazy work ethic,” says Ira Ingram, his longtime filmer. “He’ll brutalize himself to make something happen. He’ll skate something until he has baby-deer legs.”

Sheckler grimaces when asked to explain his relationship with pavement. “That relationship is super-rad when you’re rolling away,” he says, referring to the euphoric moment when a trick is finally nailed.

This is the spot in a typical cover profile where the writer lays out all the biographical backstory that helps readers contextualize where the subject has been in life. But few athletes or artists have had their early life unfold in the public eye like Sheckler. “He’s been vulnerable his entire life and everyone has been able to watch,” says Reyes. In some ways, despite his legitimate world-class talents, he is like a progenitor of the modern reality star—like a Kardashian, famous for being famous. For better or worse, key moments in his adolescence played out on MTV. (If you are too young to replay this reference in your brain, feel free to google "Life of Ryan". Or better yet, don’t.)

“Every once in a while, it takes a good slam to wake you up.”

—RYAN SHECKLER

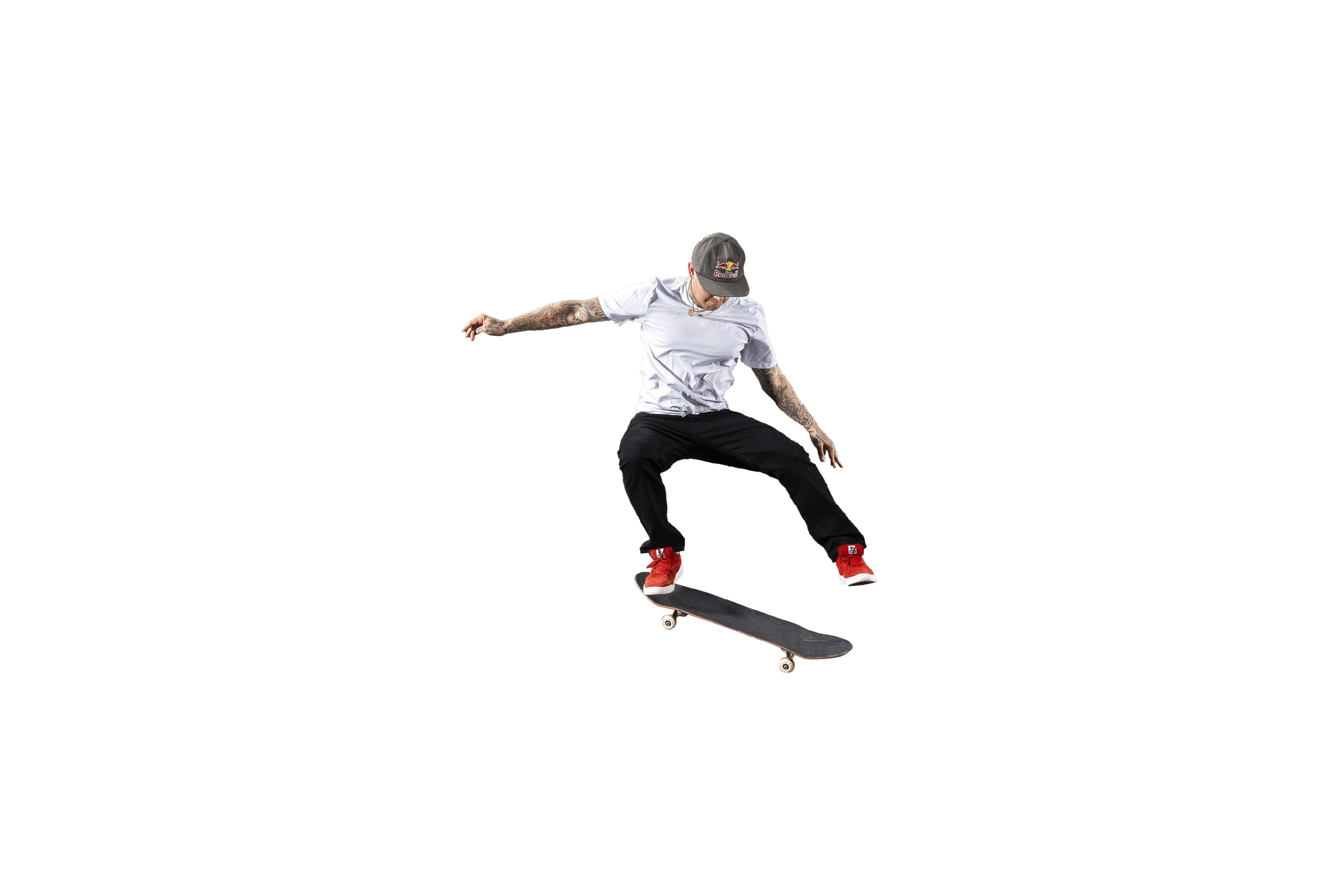

Ryan nailing a Caballeria (aka Full Cab) in the video part, You Good, filmed in Taiwan.

"Skateboarding doesn’t make you a skateboarder; not being able to stop skating makes you a skateboarder."

—LANCE MOUNTAIN

“When people talk about me, I want them to see me as a guy who helped others succeed.”

—Ryan Sheckler

He’s a different person now. He’s rooted in family and faith. He’s eating smarter and working out with purpose and sleeping better—basically doing whatever it takes to put himself in position to skate at his best. “Who he is today is 100 percent different from who he was five years ago,” says Reyes. “He’s so accomplished and that’s going to last forever. He doesn’t have to prove anything but he knows that he has to do this because he loves it.”

In that same vein, Sheckler is more committed to being a mentor, to offering younger skaters the kind of guidance that no one was in a position to offer him. He runs a brand now, Sandlot Times, which gives him more formal interaction with young talent and a clearer role to be a mentor to the next generation. In fact, when Sheckler is asked to assess his legacy, he’s emphatic that he doesn’t want to talk about his own skating. “Honestly, I don’t care about legacy anymore,” he says. “There’s something selfish about that. When people talk about me, I want them to see me as a guy who helped others succeed and helped others reach their potential. That’s how I want to be remembered.”

Sheckler is insistent that the best part of his own self-improvement is in the meaning and peace he’s gained in his personal life. But he knows it has impacted his skating, too. He’s healthier and more fulfilled and living in the moment and more clear-headed about what skating means to him. And the people who watch him skate on a daily basis say the impact is strikingly obvious.

“Ryan has always walked his own path, and his skating speaks for itself,” says Ingram, who has witnessed more of Sheckler’s path than anyone. “But the level he’s at now—honestly it’s insane.”

"Who he is today is 100 percent different from who he was five years ago."

—David Reyes

If you spend time with Sheckler, you can see that it’s true. “For a long time, I led a life that was very fast, and now I’ve learned to slow down,” he says. “For a long time, I was gripped by partying. And injuries led me to feeling down about myself and I thought that the solution for feeling down was alcohol, but alcohol is a depressant and so it only drove me deeper into a hole. And I was making people that I love worried about me, and it wasn’t fair to them or to me. And I was ready to make a change. I was ready to admit that I wasn’t in control of my life or my drinking.”

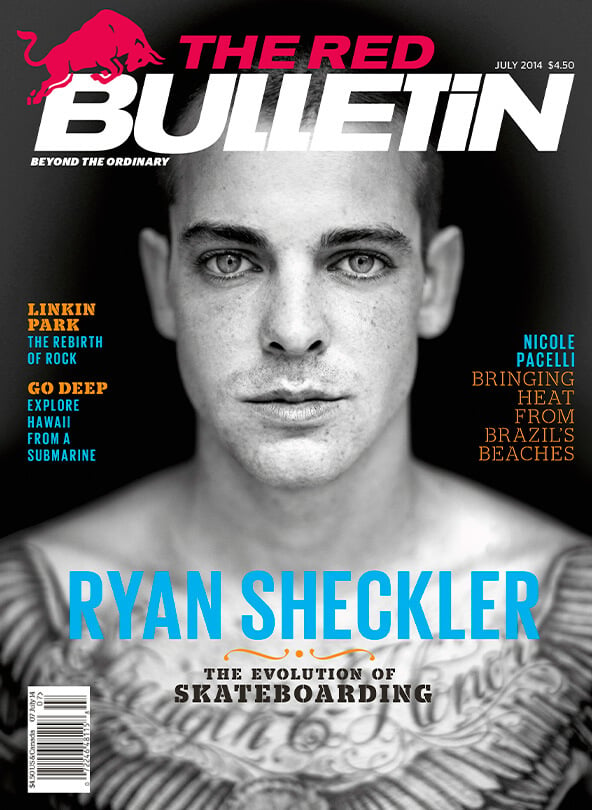

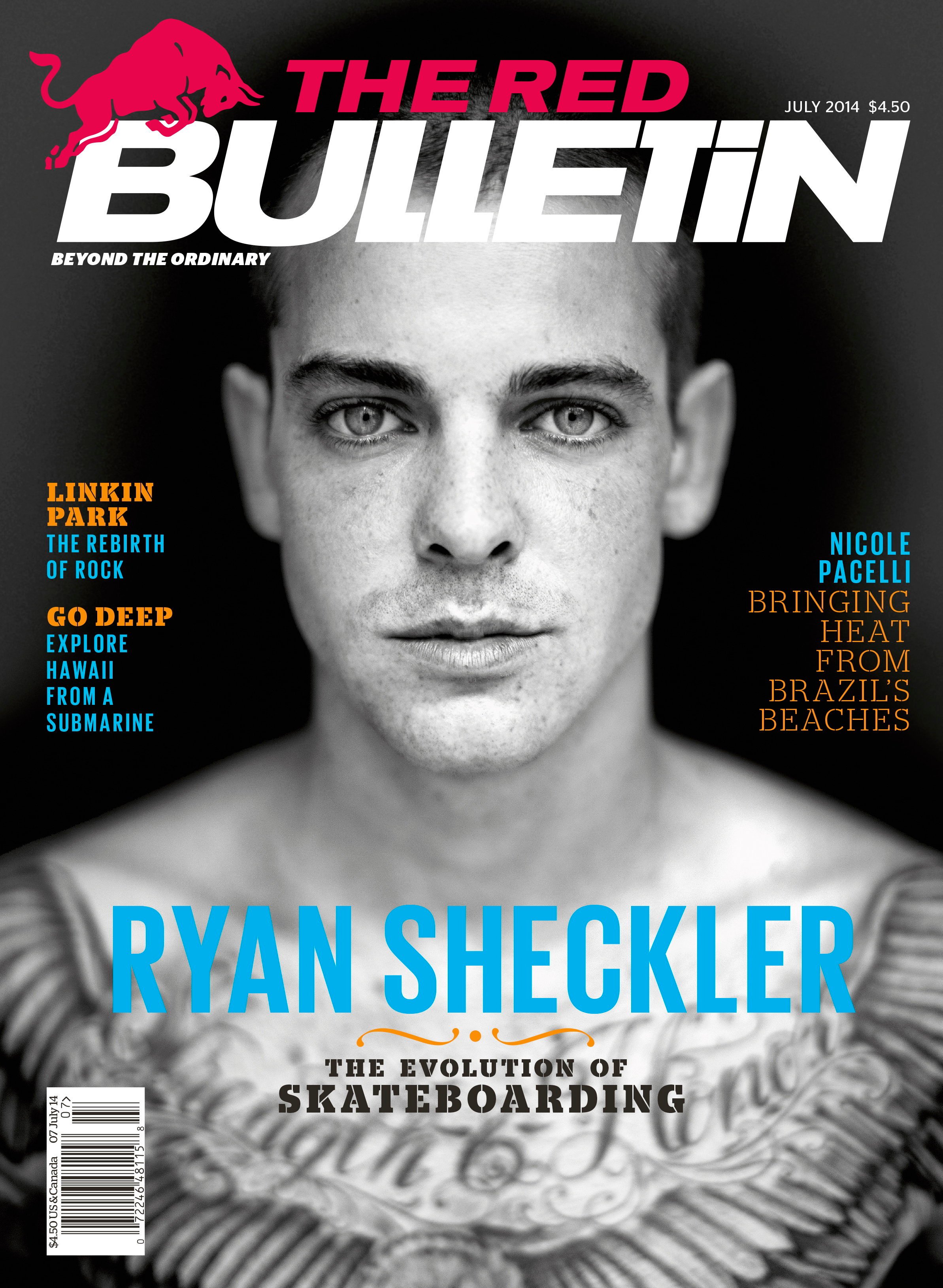

Sheckler was on the cover of this magazine in July 2014, and he holds an old copy of that issue and studies his former self. There’s a faraway look in his eyes (heightened by some dramatic eyeshadow). “I look like I’m trying to be someone that I think people want me to be,” he says. “It’s like I am trying to be tough or I didn’t know what I wanted to be. I felt like a puppet at this point. Just going where I was told to go. And I think that’s where a lot of my drinking problem came into place—I was just trying to escape and find something that would quiet the noise in my head.”

The flat-screen in the living room is set to a channel playing Christian rock. He feels like there’s no contradiction between listening to Christian ballads and skating like a punk rocker, no inconsistency in studying the New Testament and then bungeeing himself across a concrete abyss in the afternoon. Who’s to say he’s wrong about that?

Certainly not his buddy David Reyes, who says that skate culture is more open to pros like Sheckler being their true selves. “I’ve told this to Ryan and other OG pros,” he says. “Fans just want to see you be you. With Ryan they want to see the kickflip and the kickflip indy, and beyond that, there’s less judgment now.”

Sheckler feels no awkwardness or shame discussing his struggle with alcohol abuse. There has always been a hard-partying side to skate culture and a sense that there’s something uncool about talking openly about sobriety. Sheckler presently gives zero shits about those things; he just wants to be open about his own experience without telling anyone else what to do.

“When I first started filming with Ryan, it was before all this, and he had a party lifestyle that ran parallel to his skating life,” says Ingram, noting that it was (and is) far from uncommon for folks to start cracking beers long before the end of a skate session. “All I’d really say about this now is that he’s the happiest I’ve ever seen him.”

"For a long time, I led a life that was very fast, and now I’ve learned to slow down."

—RYAN SHECKLER

The central space in Sheckler’s home has an open floor plan, and visual cues of how his life has radically changed are all around. His wife, Abigail, sits in the living room, with their daughter, Olive, sleeping nearby. There is an open Bible on the dining room table and a more ceremonial Bible on display in the living room below a framed rendering of Jesus Christ. (There is also a large framed black-and-white photograph of Sheckler skating on a crowded freeway that has a considerably more secular vibe.)

Abigail gave birth at home on March 3, exactly one year to the day after she and Ryan got married. “It was a little scary when Olive came out,” Sheckler says. “She wasn’t breathing right away, but neither was I when I was born, so she’s taken after her daddy right out of the gate. The actual process of her being born was super gnarly in the best way—it’s the craziest thing I’ve ever seen.” He shares a quick smile with his wife and adds that he hopes to have “a few more.”

When he’s talking about his baby and his devotion to his faith and his recent experiences with sobriety, there’s an ease to the way he discusses these potentially thorny topics. Sheckler isn’t afraid to be honest and vulnerable about his struggles and revelations, but he also has no interest to preach or overdramatize them. “I’m trying to live by attraction rather than promotion,” he says. “I don’t want to tell people they need to go to church. I’m not trying to force things down people’s throat—I just want to be a man of my word, be a man of action.”

Sheckler was back. And over time, he realized that he was mentally and physically ready to film a major part. In March 2020, he visited Red Bull HQ in Santa Monica to finalize the plan for this project and the adjacent short film. He was fired up and ready to go.

But it turned out that it was the day before that office—and basically the world—shut down, as the pandemic changed life as we knew it. Nothing went to plan after that.

Summer 2023

aged

Won the first of

seven X-Games medals.

12

12

aged

Landed His First Kickflip

6

6

2014

2014

2023

2023

Won the first of seven X-Games medals

13

13

yo

yo

landed

his first

kickflip

6

6

yo

yo

Began working on new skate part

2020

2020

trip to Taiwan with Zion Wright and Jamie Foy

2018

2018

Ryan says he's broken more than 12 bones in his career.

12

12

using a bungee It can get Ryan up to

25-30

25-30

mph

mph

THE ROAD TO RECOVERY

A PHYSICAL AND METAPHYSICAL HOUSECLEANING

THINGS ARE FALLING INTO PLACE

Watch Rolling Away

CLEAR

FREE AND

Ryan Sheckler has found something amazing: Himself.

Words: PETER FLAX

Photography: ATIBA JEFFERSON

It’s tricky to decide where to begin the story of Ryan Sheckler’s hard-fought journey to find peace.

Maybe it starts with him writhing and screaming at the bottom of a hulking concrete staircase in Pomona, California, as he reels from yet another awful bone-and-tendon-snapping impact. No doubt, the skater’s narrative often has been propelled by how he has willed himself back to his feet after getting pummeled.

Or perhaps it opens with his second trip to rehab. Sheckler had been sober for a few years and thought maybe he could drink with moderation. He was wrong about that. But this time he felt something click inside—a deep yearning to alter the trajectory of his life—and now a very public figure who spent a solid chunk of two decades feeling pretty lost has found a better foothold.

“Life is hard for a reason

—we’rE supposed to learn,"

—RYAN SHECKLER

THE PRELUDE

THE PRELUDE

THE PRELUDE

“Inner peace builds confidence,” says fellow skate pro David Reyes, one of Sheckler’s closest friends. “Inner peace allows you to be present in the moment. He’s always been a Nitro Circus baby, someone born to jump off things and take risks, but now Ryan is skating with more confidence than I’ve ever seen.”

As this story goes live, the finishing touches are being applied to an ambitious skate part and a documentary unpacking Sheckler’s tumultuous journey, aptly called "Rolling Away". Both projects, which are expected to drop in July, have been three years in the making, delayed and informed by the pandemic, an injury that could have been career ending, rehab and the roller-coaster known as life. True to his obsessively perfectionist nature, he’s trying to nail a couple final tricks, including one that would instantly join his greatest hits, before setting that content free. Rest assured that domestic and existential bliss have not quieted Ryan Sheckler’s hunger to explore the boundaries of physics and courage. It’s more like he’s free to go for it.

"INNER PEACE ALLOWS YOU TO BE PRESENT IN THE MOMENT."

—David Reyes

Photo credit: Tim Aguilar

Sheckler, who long ago gained fame for skating the gnarliest shit and acting like a rock star, has turned his gaze inward, finding things he didn’t realize he needed. Sobriety. Faith. Marriage. Fatherhood. Balance. And perhaps above all, peace. You can see it as he holds his baby and whispers in her ear.

And, fans will be stoked to hear, you can see it when he skates. Though it long has been true that Sheckler has nothing to prove, he’s liberated to express himself in ways that feel new. The physical and metaphysical housecleaning has reinvigorated him as a skater. The 33-year-old veteran— who has been performing at the highest level for two decades and helped orthopedic surgeons put their kids through college and juggled as much love and hate from skate culture as any pro ever—is seeing a new clarity and drive in his skating life.

But while the structure of this story’s prologue remains up in the air, the broader contours of his journey and even his destination are in sharp focus. Ryan Sheckler is in a good place. “Until recently, my identity—my whole life—has been tied to skateboarding,” he says later, as his daughter, Olive, snoozes in a rocker nearby. “I never addressed who Ryan was as a person. And by doing that, all of these doors have opened and all these situations that used to baffle me and take me for a complete loop have beome completely manageable.”

"Until recently, my identity—

my whole life— has been tied

to skateboarding."

—RYAN SHECKLER

Or maybe the story begins as Sheckler opens the front door to his home with a 19-day-old infant cradled in his right arm. His eyes look a little heavy—after all, the skater and his wife are trapped in a sleep-deprivation experiment—but there’s an ease to his gaze. Like he’s about to launch a huge gap and he just knows he’s going to land it. Somehow, he’s in his element. The guy that friends and fans sometimes called Sheck Daddy has undeniably manifested that title.

“But everything else is just a brutal divorce, you know? It’s gnarly. I was counting the other day—it’s over 12 broken bones, more torn ligaments than I can remember and six major surgeries, concussions. It’s all pain.”

Sheckler has been through the cycle of injury, surgery and recovery enough times to know how much it can impact his mental health. “I’ve probably spent five years in total of my life recovering,” he admits. “That’s where my mind starts going a little bit crazy and the questions start coming up. ‘Am I made for this? Do I even want this? What am I doing?’ And those questions are super gnarly, especially when you’re already down and you can’t do anything.”

"He’ll skate something until he has baby-deer legs.”

—Ira Ingram

Won the first of seven X-Games medals

12

12

yo

yo

landed

his first

kickflip

6

6

yo

yo

Won the first of seven X-Games medals

13

13

yo

yo

landed

his first

kickflip

6

6

yo

yo

For those seeking context, here’s a 170-word summary: He ripped a kickflip at 6. A year later, he had legit sponsors. He won the first of seven X-Games medals when he was 13. Then came reality shows and TV commercials, A-list fame and millions of dollars. He was skating hard, winning contests and releasing sick clips, flying private jets and collecting supercars and partying hard and polarizing skate culture. He was a teen superstar on a wild adventure with no mentors or a road map, living large with a major IDGAF attitude. (In a 2011 interview with "ESPN The Magazine" he leaned into the friction with core skate fans: “I want to give them more reasons not to like me.”) But through it all, even when folks were dissing him like he was the Justin Bieber of skating, even the biggest haters couldn’t deny that his clips were off the charts. People still talk about his 2008 kickflip at the so-called Costco Gap in Laguna Nigel, clearing a fence and a monstrous 16-foot drop with shocking nonchalance.

Along the way, there were so many huge tricks and huge impacts. “He’s got a crazy work ethic,” says Ira Ingram, his longtime filmer. “He’ll brutalize himself to make something happen. He’ll skate something until he has baby-deer legs.”

Sheckler grimaces when asked to explain his relationship with pavement. “That relationship is super-rad when you’re rolling away,” he says, referring to the euphoric moment when a trick is finally nailed.

This is the spot in a typical cover profile where the writer lays out all the biographical backstory that helps readers contextualize where the subject has been in life. But few athletes or artists have had their early life unfold in the public eye like Sheckler. “He’s been vulnerable his entire life and everyone has been able to watch,” says Reyes. In some ways, despite his legitimate world-class talents, he is like a progenitor of the modern reality star—like a Kardashian, famous for being famous. For better or worse, key moments in his adolescence played out on MTV. (If you are too young to replay this reference in your brain, feel free to google "Life of Ryan". Or better yet, don’t.)

“Every once in a while, it takes a good slam to wake you up.”

—RYAN SHECKLER

Ryan nailing a Caballeria (aka Full Cab) in the video part, You Good, filmed in Taiwan.

Watch Rolling Away

—DAVID REYES

“One thing that comes with inner peace is that you simply stop caring what anyone thinks of you.”

In his mind, the journey that would lead him to sobriety, the Bible, his wife, a baby, and to skating with new clarity and joy began right there in Pomona, as he recoiled in agony.

Sheckler knew what would come next. Pain. Grinding physical therapy. Creeping self-doubts. He knew that all he could do is obsessively recover and train to be ready when the next opportunity came.

That opportunity came sooner than he or anyone would have guessed. Later in 2018, Sheckler was invited to join fellow Red Bull pros Zion Wright and Jamie Foy on a trip to Taiwan. Even though he wasn’t 100 percent healed, he found himself in a great headspace and would up nailing all sorts of clips. The highlight of that trip came when he pulled off a high-consequence taildrop off a Taipei bridge into a quarterpipe that was flanked on both sides by highway traffic. “That taildrop was as scary as anything he’s ever done,” says Ingram, who filmed the trick. “My hands were literally shaking so I needed to lean against something as I shot it.”

Even top pros were blown away. “One word comes to mind seeing that taildrop: ‘psycho,’ ” says pro Paul Rodriguez, aka P Rod, Sheckler’s longtime former teammate with Plan B. “Like that was insane.”

Sheckler was back. And over time, he realized that he was mentally and physically ready to film a major part. In March 2020, he visited Red Bull HQ in Santa Monica to finalize the plan for this project and the adjacent short film. He was fired up and ready to go.

But it turned out that it was the day before that office—and basically the world—shut down, as the pandemic changed life as we knew it. Nothing went to plan after that.

trip to Taiwan with Zion Wright and Jamie Foy

2018

March

Began working on new skate part "Lifer"

2020

Began working on new skate part

2020

2020

trip to Taiwan with Zion Wright and Jamie Foy

2018

2018

“But that fall was the catalyst for me to take a deep dive into myself.”

—RYAN SHECKLER

In "Rolling Away", a few legendary pros try to describe the abusive relationship committed skaters have with pavement. “Skateboarding is terrible for your body,” says British skate pioneer Geoff Rowley, no stranger to brutal slams. “And it chips away like a hammer and chisel.”

Meanwhile, fellow American icon Tony Hawk (who was a surprise guest at Sheckler’s 6th birthday party) reflects on the commitment that the hammer and chisel demand. “When you first start to skate, there’s sort of a moment of recognition and the threshold, where the first time you get hurt seriously,” says Hawk, who like Sheckler has seen a surgeon or two. “That’s the moment where it’s like, do you really love this enough to keep doing it?”

As "Rolling Away" documents, Sheckler faced two serious injuries in the past five years that challenged his resolve. The first came in 2018 in Pomona, where an attempt to grind the cement railing of an 18-step staircase ended with him crumpled on the ground. He pulverized the bones and tendons in his left ankle and also broke the L1 vertebra in his lower back. “I don’t really talk about this slam because it was so traumatic,” says Sheckler, who soon would be back in a surgical suite.

THE ROAD TO RECOVERY

"Actually, for the first time, I have a full life.”

A long day with Sheckler is drawing to a close. His wife is cradling his baby. His mother, who helps run his various business enterprises, sits at the head of the dining room table firing off emails. He is rubbing his eyes. Ryan Sheckler is tired because he spent part of the night half asleep on the floor of the nursery. But he’s feeling alive and well because so many things have fallen into place for him. He’s grateful for that horrible slam in Pomona and how it nudged his trajectory in a better direction. The products of reawakening are all around him.

“It feels like I could’ve missed all of this,” Sheckler says, waving his arms at the family around him and at things that can be felt and not seen. “It feels like I could’ve missed it all. But by changing one thing, which meant I had to change everything, I have a full life again.”

He pauses, then corrects himself.

"think I’m just curious still, and I’m also addicted to that adrenaline rush of healthy fear.”

—Ryan Sheckler

Sheckler freely admits this quest presses many of the same buttons as any other addiction—not just with the narcotic rush of rolling away from an impossibly hard trick, but all the heartache and tense moments that precede it. “I think I’m just curious still, and I’m also addicted to that adrenaline rush of healthy fear,” he says. “I’m addicted to the whole process. It’s the drive. It’s what music I’m going to listen to on the way down. Sometimes I don’t listen to music; sometimes it’s one song on repeat. It’s all very different and it’s very hard to calculate what the right day is to do it, so everything’s a guess. It’s kind of like the lottery, you know?”

The part and the film are almost done—but not done. In particular, Sheckler is intensely focused on one trick—it’s a massive gap in northern San Diego County. Maybe he’ll have nailed by the time you read this. Maybe not. “I hope to get this last trick and I believe I will,” he says. “I’m scared of it, you know? But it’s a healthy fear. I cannot let this thing go. And I think that’s what’s made me a skateboarder and that’s why I’m still a skateboarder today.”

Reyes has seen the spot, and he also knows the kind of obsessiveness that can be wrapped around rolling away from a trick that a skater feels certain should end his next part. “The caliber of the spot has this aura,” he says. “With an ender, it has to be the craziest shit you’ve ever done. It has to be monumental, something that will live in the skate books forever. I know where Ryan is at now—it’s like being in a nightmare until you get the trick.”

"We are talking about intense physics—it’s like he’s getting fired out of a cannon.”

—Ira Ingram

That’s when Sheckler learned he had completely severed his ACL. So it was back to the surgeon and the couch and the PT and the creeping self-doubt. “Ryan isn’t old by any means,” says Ingram. “But still, a torn ACL in your 30s can be a career ender for a pro skater.” Sheckler attacked his rehabilitation to get well as fast as possible. He amped up his weight training to add muscle mass as body armor. He did everything he could to stay busy because it took 14 long months before he could really start doing heavy tricks again. That whole period was tough. He lost his grandmother during that grinding recovery. “She was my best friend,” Sheckler says. He had plenty of reasons to start drinking again. But he didn’t.

By the time he got back at it, so much about his life was reoriented in a different and better way. He was sober and engaged and going to church and doing a lot of little things more mindfully. And he went out with an intense eye to execute tricks that pushed his own envelope. Ingram says Sheckler has been playing with bungees that enable him to launch up features that in the past he would have launched himself down. “We’re using a bungee that’s off the market now because it’s so dangerous,” Ingram says. “It can get Ryan up to 25 or 30 miles per hour.

As the upcoming skate part and the film "Rolling Away" will demonstrate, Sheckler still has something to prove—not to fans or posterity but to himself. It’s been more than three years since these projects were born, and seeing them through has required more perseverance than he could have imagined.

The earliest weeks of filming, which coincided with the start of the pandemic, required significant improvisation, as Sheckler and Ingram sought out some truly isolated spots to nail down clips. Nonetheless, these were intensely productive months, yielding one quality clip after another.

But that early momentum came to a painful and screeching halt three months later in National City, California. Sheckler had his eye on a high-risk ender, a dramatic clip that would appear near the end of his part to showcase his best work, but he suffered a hard landing before he could even give it a shot. Warming up with an easier trick, he launched over a staircase with metal railings on both sides and landed awkwardly on a sloped concrete embankment, with the brunt of the impact loaded on his left knee. True to form, Sheckler, who says it felt like a “super gnarly deadleg,” kept skating that session, even nailing a couple more tricks. He can admit now that he was in a state of denial; he didn’t get an MRI of that joint for a month and a half after skating those six weeks in a knee brace.

-Ryan Sheckler

using a bungee It can get Ryan up to

miles per hour

25-30

Ryan says he's broken more than 12 bones in his career.

12

using a bungee It can get Ryan up to

25-30

25-30

mph

mph

Ryan says he's broken more than 12 bones in his career.

12

12

THINGS ARE FALLING INTO PLACE

Check out Ryan’s new video part Lifer

Summer 2023

The flat-screen in the living room is set to a channel playing Christian rock. He feels like there’s no contradiction between listening to Christian ballads and skating like a punk rocker, no inconsistency in studying the New Testament and then bungeeing himself across a concrete abyss in the afternoon. Who’s to say he’s wrong about that?

Certainly not his buddy David Reyes, who says that skate culture is more open to pros like Sheckler being their true selves. “I’ve told this to Ryan and other OG pros,” he says. “Fans just want to see you be you. With Ryan they want to see the kickflip and the kickflip indy, and beyond that, there’s less judgment now.”

2014

2014

2023

2023

"For a long time, I led a life that was very fast, and now I’ve learned to slow down."

—RYAN SHECKLER

The central space in Sheckler’s home has an open floor plan, and visual cues of how his life has radically changed are all around. His wife, Abigail, sits in the living room, with their daughter, Olive, sleeping nearby. There is an open Bible on the dining room table and a more ceremonial Bible on display in the living room below a framed rendering of Jesus Christ. (There is also a large framed black-and-white photograph of Sheckler skating on a crowded freeway that has a considerably more secular vibe.)

Abigail gave birth at home on March 3, exactly one year to the day after she and Ryan got married. “It was a little scary when Olive came out,” Sheckler says. “She wasn’t breathing right away, but neither was I when I was born, so she’s taken after her daddy right out of the gate. The actual process of her being born was super gnarly in the best way—it’s the craziest thing I’ve ever seen.” He shares a quick smile with his wife and adds that he hopes to have “a few more.”

When he’s talking about his baby and his devotion to his faith and his recent experiences with sobriety, there’s an ease to the way he discusses these potentially thorny topics. Sheckler isn’t afraid to be honest and vulnerable about his struggles and revelations, but he also has no interest to preach or overdramatize them. “I’m trying to live by attraction rather than promotion,” he says. “I don’t want to tell people they need to go to church. I’m not trying to force things down people’s throat—I just want to be a man of my word, be a man of action.”

A PHYSICAL AND METAPHYSICAL HOUSECLEANING

"Skateboarding doesn’t make you a skateboarder; not being able to stop skating makes you a skateboarder."

—LANCE MOUNTAIN

“When people talk about me, I want them to see me as a guy who helped others succeed.”

—Ryan Sheckler

He’s a different person now. He’s rooted in family and faith. He’s eating smarter and working out with purpose and sleeping better—basically doing whatever it takes to put himself in position to skate at his best. “Who he is today is 100 percent different from who he was five years ago,” says Reyes. “He’s so accomplished and that’s going to last forever. He doesn’t have to prove anything but he knows that he has to do this because he loves it.”

In that same vein, Sheckler is more committed to being a mentor, to offering younger skaters the kind of guidance that no one was in a position to offer him. He runs a brand now, Sandlot Times, which gives him more formal interaction with young talent and a clearer role to be a mentor to the next generation. In fact, when Sheckler is asked to assess his legacy, he’s emphatic that he doesn’t want to talk about his own skating. “Honestly, I don’t care about legacy anymore,” he says. “There’s something selfish about that. When people talk about me, I want them to see me as a guy who helped others succeed and helped others reach their potential. That’s how I want to be remembered.”

Sheckler is insistent that the best part of his own self-improvement is in the meaning and peace he’s gained in his personal life. But he knows it has impacted his skating, too. He’s healthier and more fulfilled and living in the moment and more clear-headed about what skating means to him. And the people who watch him skate on a daily basis say the impact is strikingly obvious.

“Ryan has always walked his own path, and his skating speaks for itself,” says Ingram, who has witnessed more of Sheckler’s path than anyone. “But the level he’s at now—honestly it’s insane.”

"Who he is today is 100 percent different from who he was five years ago."

—David Reyes

If you spend time with Sheckler, you can see that it’s true. “For a long time, I led a life that was very fast, and now I’ve learned to slow down,” he says. “For a long time, I was gripped by partying. And injuries led me to feeling down about myself and I thought that the solution for feeling down was alcohol, but alcohol is a depressant and so it only drove me deeper into a hole. And I was making people that I love worried about me, and it wasn’t fair to them or to me. And I was ready to make a change. I was ready to admit that I wasn’t in control of my life or my drinking.”

Sheckler was on the cover of this magazine in July 2014, and he holds an old copy of that issue and studies his former self. There’s a faraway look in his eyes (heightened by some dramatic eyeshadow). “I look like I’m trying to be someone that I think people want me to be,” he says. “It’s like I am trying to be tough or I didn’t know what I wanted to be. I felt like a puppet at this point. Just going where I was told to go. And I think that’s where a lot of my drinking problem came into place—I was just trying to escape and find something that would quiet the noise in my head.”

Sheckler feels no awkwardness or shame discussing his struggle with alcohol abuse. There has always been a hard-partying side to skate culture and a sense that there’s something uncool about talking openly about sobriety. Sheckler presently gives zero shits about those things; he just wants to be open about his own experience without telling anyone else what to do.

“When I first started filming with Ryan, it was before all this, and he had a party lifestyle that ran parallel to his skating life,” says Ingram, noting that it was (and is) far from uncommon for folks to start cracking beers long before the end of a skate session. “All I’d really say about this now is that he’s the happiest I’ve ever seen him.”

Ryan performing a kickflip at the so-called Costco Gap in Laguna Nigel back in 2008.

THE ROAD TO RECOVERY

Film provided by Mike Aldape.

Film provided by Mike Aldape.

Ryan’s 2003 gold winning X-Games run.

Ryan’s 2003 gold winning X-Games run.

Video provided by xgames.com.

Video provided by xgames.com.